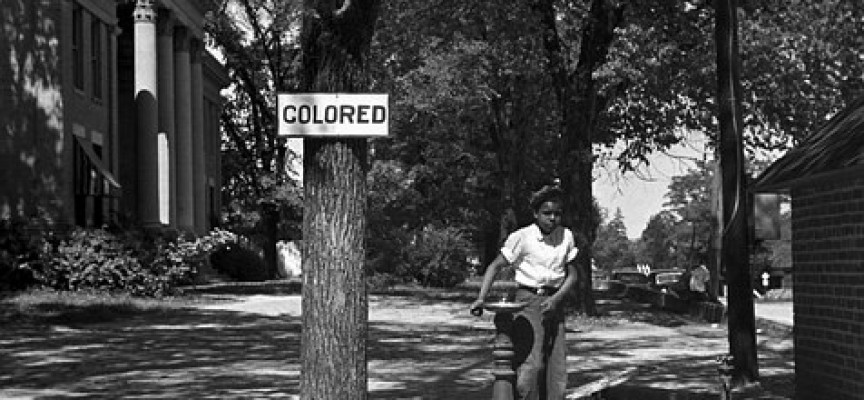

In light of the racial tensions that have continued to surface in the United States over the past two years, white American Evangelicals should embrace the opportunity to reassess our views of race and reconsider how we might serve as agents of Christian healing and reconciliation.

In our reassessment, we will discover that we have not made as much progress in overcoming racism as we might have thought. One reason is that many of us have not crafted a biblically informed and conceptually clear model for understanding race, racism, and racial unity. When we give any sustained thought to race and racism, we tend to adopt secular models (offered to us by our favorite cable news networks) and assume that they are compatible with a Christian framework for thinking through the issues.

In his book, Beyond Racial Gridlock, University of North Texas sociologist George Yancey argues that four secular conceptual models dominate the discussion of race and racism. Each of the models are undergirded by flawed conceptions of racism that do not account for the full biblical teaching on sin and redemption. None of the models are shaped by the Bible’s storyline. Therefore, each of them is insufficient for addressing race and racism.

In this post, I will outline the two flawed conceptions of racism and the four flawed models for overcoming it, before concluding with some brief reflections on a better way for white Evangelicals to conceive of racism and racial unity.

Two Flawed Conceptions of Racism

Underlying the four deficient models for overcoming racism are two predominant but flawed conceptions of racism: individualism and structuralism.

Individualism

One flawed conception, individualism, “views racism as something overt that can be done only by one individual to another. This definition relies on the concept of freewill individualism [which] holds that racial strife is the result of an individual choosing to act in a racist manner” (20). Citing work by Michael Emerson and Christian Smith, Yancey notes that white evangelicals are especially prone to adopt this definition because evangelicals have a strong concept of personal sin (21).

Structuralism

The other flawed conception, structuralism, holds that “society can perpetuate racism even when individuals in the society do not intend to be racist. The structuralist viewpoint rests on the idea that humans are affected by the social structures in which they live.” (21–22) Again citing Emerson and Smith, Yancey observes that blacks are more likely than whites to be structuralists. Yet the difference is even more acute among evangelicals: “white evangelicals are even more individualistic than other whites, and black evangelicals are even farther apart than whites and blacks in general” (23).

The problem with these conceptions is that they both ignore the spiritual and theological dimensions of race and place too much emphasis on a particular side of the individual/structural coin. Scripture teaches that sin is committed by individuals, but it also teaches that our sin and idolatry corrupt and misdirect social and cultural institutions. So we should expect to find racism both in individuals and in structures.

Four Flawed Secular Models for Overcoming Racism

Emerging from these two definitions of racism are four deficient secular models for overcoming racism. Each is insufficient for building a Christian understanding for overcoming racism and fostering racial unity-in-diversity.

Colorblindness

The first model is colorblindness. Its proponents believe that, “to end racism, we have to ignore racial reality. Advocates of colorblindness contend that efforts to alleviate our…racial divide only elevate the importance of race, which in turn only reinforces the negative power of race in our society” (29–30). Politically conservative Christians often baptize this secular view because human beings are defined primarily by the imago Dei rather than by race, and are (largely) responsible for their own flourishing in society.

The strengths of this model are twofold: it wants to stop individuals from being racists and it helps minorities to avoid looking for racism where it does not exist (32–33). Yet this model is flawed in several ways. Historically, it tends to ignore the negative effects of racism handed down from generation to generation. In relation to the biblical doctrine of humanity, it neglects the positive significance of human diversity and tends to avoid even discussing racial equality (34–36). In relation to the doctrine of sin, it tends to focus on individual person’s sins while ignoring the way our society’s past and present racial sins corrupts and misdirects social and cultural institutions. In other words, it tends to locate the consequences of sin merely in interpersonal encounters but not in society and culture (39). For these reasons the colorblind model can unconsciously perpetuate racism.

Anglo-Conformity

The second model is Anglo-conformity. This model shares some similarities with the colorblindness model, but is unique in emphasizing its view that racism and racial tension will be resolved when persons of color have the sort of upward mobility that many whites have. In other words, racial problems are primarily economic and should be resolved primarily through government-sponsored programs.

Positively, this model acknowledges tough economic realities and it looks for minorities to take the lead in solving the ills of their families and neighborhoods (45–46). However, the model has several weaknesses: it puts too much emphasis on economic solutions, wishes for minority cultures to accommodate themselves to white culture, and finds itself so tied to a certain view of capitalism that any alternate economic proposals find no place in the discussion. Yancey argues that it comes up short of the humble nature of Christianity, which eschews rather than gobbles up power (51).

Multiculturalism

The third model is multiculturalism. This model wishes to build a “society in which distinct racial and ethnic groups preserve their own identities.” Examples of multiculturalism include the use of multiple languages on official government forms, and the representation of diverse cultures and subcultures in public school curricula. On the positive side, this model helpfully tries to correct many of our society’s Eurocentric overemphases (55), encourages minorities to both understand and appreciate their own cultures as well as to critique them from within.

Yet ironically, under the multiculturalist model minorities tend to degrade the culture of the majority (57). Yancey finds this reality working its way into Christian perspectives such as Randy Woodley’s and Clarence Shuler’s (60–61). But the deepest problem with this model is how its relativistic impulse overrides Christian claims of moral right and wrong. Thus, minority cultures go un-critiqued while the majority culture is perpetually on the hot seat.

White Responsibility

The fourth model is white-responsibility. This model rightly recognizes the historic racial sins of whites against blacks. It places the blame for racism squarely on whites (64). In this perspective, “racial minorities can have prejudice, but they cannot be racist because racism requires structural power” (65). The dominant group, i.e. whites, hold the structural power and they alone are racists. This model emerged from ethnic studies programs in certain American colleges and, in turn, gave birth to critical race theory, which argues that racism is in inherent to American culture (65). Proponents of white responsibility, therefore, seek to change the power structures in our country.

This model’s strength is its revelation of the ways a single group can overtly and covertly dominate social groupings and cultural institutions. However, this model is wrong to discount the responsibility of racial minorities: if, as they argue the majority is always at fault, then minorities have no responsibility. It “it ignores the fact that all people––majority or minority––are sinners. As such, it is hard to call the Christian version of this model “Christian.” It also alienates whites which further contributes to racism in its individual and structural manifestations.

A More Excellent Way

As Evangelicals we must find “a more excellent” way to conceive of racism and to foster racial reconciliation and unity. We must acknowledge that individuals commit racist sins, but also that a society’s sins coalesce to corrupt and misdirect that society’s cultural institutions, which in turn (mis)shapes the individuals of that society. So racism is found at both the micro and macro levels.

A fuller understanding of racism will enable us to conceive of a better model for fostering racial reconciliation and unity. That model will recognize that God’s original creational design includes and invites unity-in-diversity, just as his plan for the new heavens and earth involves a resplendent ethnic and cultural unity-in-diversity. It will refuse to assign blame entirely on minority or majority group members, but instead will call both to repentance and entrust both with responsibility.

There are many ways in which white Evangelicals admirably represent Christ and his gospel. I am convinced, however, that overcoming racism is not yet one of the ways that we represent him admirably. Let us pray that the King of the nations will help us to repent of our sins, repair our ignorance, and carve out a path of gospel faithfulness for the sake of our souls, for the love of our black brothers and sisters, for the health of the church, and for our witness to the world.

Subscribe

Never miss a post! Have all new posts delivered straight to your inbox.

Dr. Ashford, you criticize the “white-responsibility” model for “discount[ing] the responsibility of racial minorities.” In the context of an article addressed to the need for “white American Evangelicals… [to] embrace the opportunity to reassess our views of race and reconsider how we might serve as agents of Christian healing and reconciliation,” how do you imagine racial minorities to be responsible for racism in America?