Please allow me to serve advance notice of a major event: the newly formed Center for Hebraic Thought (CHT) at King’s College in New York City. The CHT equips Christians to study the Bible seriously, making applications to all sectors of society and spheres of culture. In many ways, their mission and vision aligns with the goals of this website.

For that reason, I asked the CHT’s Director, Dru Johnson, to answer a few questions about the CHT, focusing especially on the Bible’s relevance to the discipline of philosophy. Whereas many philosophers who are Christians think that the Bible should not be a source for the discipline, Dru argues that Scripture should be the starting point for a Christian’s study of philosophy. That puts him in the company of many great philosophers of the past, such as Augustine, Pascal, Hamann, Kierkegaard, Chretien, and Plantinga. Here is my conversation with Dru:

1. Dru, you and the CHT promote the view that Christians need to study philosophy and, in so doing, they should start with their Bibles. Before we discuss what you mean by this statement, talk to us about how you became interested in the discipline of philosophy in the first place.

I was a fairly new Christian in seminary and I had a lot of questions. Most of those were answered, but I always gravitated toward understanding the principles behind our confidence in science, which theological questions to pursue, etc. I read a book by a scientist-turned-philosopher named Michael Polanyi and that captured my desire to think about the principles behind the practical matters of life.

I finished seminary, continued to work as a pastor, and did an M.A. in analytic philosophy at the University of Missouri (St. Louis). Although I was learning from mostly atheist philosophers, they were genuine and welcomed Christians like me into the discussions. They taught me that no one really holds the trump card of logic or rationality. We’re all putting our faith in some mysterious explanation, even mathematicians cannot explain their own field philosophically without appealing regularly to mystery.

At the same time, I was teaching Bible to children and college-aged adults in our church. I saw that Scripture was also creating an intellectual world as formative, rigorous, and interesting as anything the Greek or European philosophers did. No one was writing about this, so I eventually completed my Ph.D. looking at Scripture’s theory of knowledge.

2. What do you mean when you say that the Bible should be the starting point for a Christian’s study of philosophy?

Philosophy doesn’t have a single definition. In general, we could say that philosophy studies the nature of things apart from our historical experience of them. So, philosophy studies the nature of justice apart from any particular act of justice or injustice. The same with knowledge, ethics, logic, beauty, politics, and even the nature of nature itself.

Everything we feel passionately about, from saying, “that was a horrible movie” to “the government shouldn’t do that” has philosophical roots. We all carry some principles about the nature of a “good movie” or “the government’s responsibility” and our ideas might be principled and useful or horribly scattered reactions to our experiences.

As creatures of the living God, Scripture asks us to consider the nature of our world apart from our isolated experiences and to live according to those principles. We should study philosophy, if for no other reason, so that we can clearly distinguish biblical teaching from mere cultural babbling. But the biblical authors write in such a way that they want us to grasp the nature of justice, beauty, knowledge, governance, and more from their perspective. And we don’t have to be geniuses to do study biblical philosophy. It’s for all of us, from farmer to firefighter, children to baby boomers.

So yes, we should have more principled explorations in our churches about the nature of our world and not be afraid to learn the philosophies of our American culture, for instance. However, we should begin to learn philosophy under the instruction of the biblical authors, so that we can have a basic grasp on the nature of justice before we start naively mixing it up with American views of justice, for instance.

3. Contrast your view with a scholar who says that the defining difference between theology and philosophy is that, while both disciplines attempt to answer the “big, big” questions in life, philosophy does so without drawing upon religious traditions and documents. Why is your view the better view? What type of philosophical “fruit” will it bear that other philosophical methods will not?

Plato and Aristotle based their philosophical views in Greek theologies about the nature of God and gods, receiving instruction from spirits and oracles at times. To think that philosophy doesn’t involve theological assumptions is quaint, even if the assumption is that there is no god or that humanity is divine. Everyone who runs into a fresh atheist knows that there is an obsession with some version of the problem of evil: how a good God could allow such evils in the world.

However, as Scott Peck once pointed out in People of the Lie, why is no one equally obsessed with the problem of good? Why do we think good is the way things ought to be. We desire good things for ourselves and others without ever questioning the theological principles upon which a notion of “good” rests.

The Greek philosophers took this question of “the good” seriously. So did the Hebrew philosophers (which includes most of the NT authors). Making an absolute separation of theology from philosophy isn’t helpful or accurate to how we think. That said, I can certainly see the reasons why we might want to define some issues more as a philosophical problem (such as logic or math puzzles) and others as theological (such as the puzzling logic of the Trinity in Christian theology).

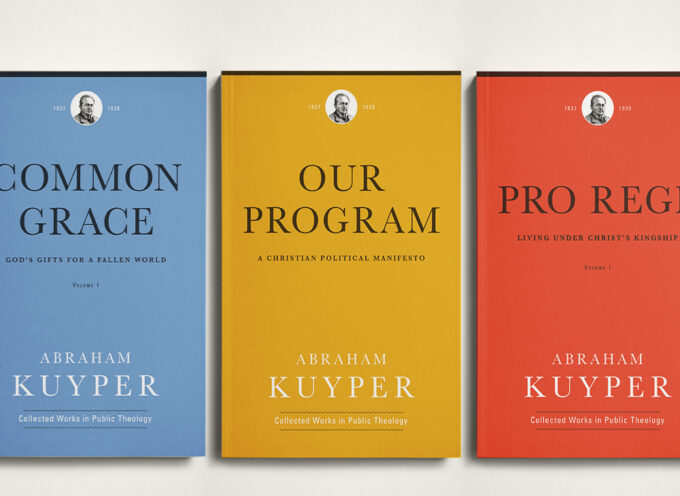

4. Who are some examples of exemplary philosophers, thinkers who draw upon Scripture in constructing their philosophies?

For examples of biblically-informed Jewish philosophy, good examples are Yoram Hazony’s The Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture, which thinks philosophically about the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) from a Jewish perspective; Joshua Berman’s work Created Equal: How the Bible Broke with Ancient Political Thought; and Jeremiah Unterman’s Justice for All: How the Jewish Bible Revolutionized Ethics.

There are, of course, many Christian Scholars who explore the intellectual world of Scripture. A few contemporary texts include (indulging the moment to include my own work): Peter Leithart’s work at theopolisinstitute.com; Jonathan Pennington’s Jesus the Great Philosopher (forthcoming); my own book, Scripture’s Knowing and Human Rites, which explores Scripture as philosophically formative; and my forthcoming book Biblical Philosophy: A Hebraic Approach to the Old and New Testaments, which argues that biblical literature is a form of spiritual philosophy.

5. What are the best ways for the readers of bruceashford.net to connect with, and benefit from, the work of the CHT?

Readers can find essays, podcasts, and videos at our magazine The Biblical Mind (biblicalmind.org).

Subscribe

Never miss a post! Have all new posts delivered straight to your inbox.