Please allow me to serve advance notice: if Christians in the United States are going to keep their moorings in the 21st century, they will need to return continually to their roots in Christian Scripture and the Great Tradition. This is true in every sphere of culture, including the arts and sciences, business and entrepreneurship, politics and economics, and scholarship and higher education.

Yet, it is this last sphere—scholarship and higher education—that is heavy on my mind. In general, this is because I have seen the way “secular” and pagan scholarship has corrupted higher education. In particular, however, it is on my mind because I am part of a group of scholars—the Transdisciplinary Group—who met this past week and who wish to encourage “radical Christian scholarship” among Christian scholars and institutions of higher education.

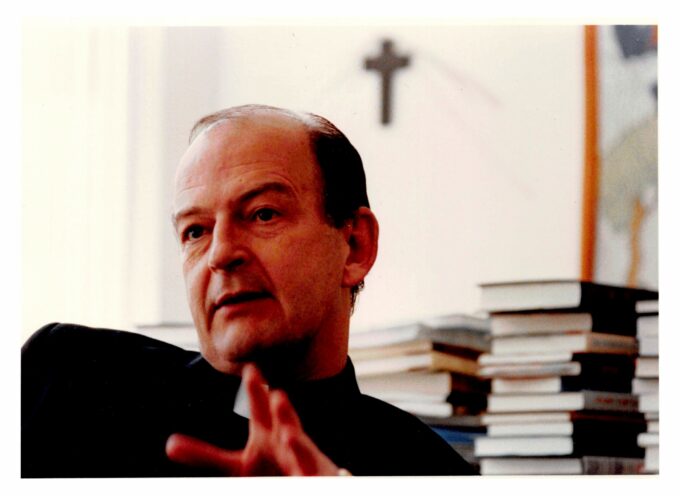

The plenary speakers included Peter Leithart, Kevin Vanhoozer, Craig Bartholomew, Eric Johnson, C. Stephen Evans, Mary Poplin, and Esther Meek, and the MC of the conference was yours truly. Although the speakers represented a diversity of denominations and schools of thought, we are unified around our belief that God’s revelation should shape our scholarship radically (at its roots) in at least four ways:

1. Modernism has caused fragmentation and misdirection in higher education.

The general consensus of Transdisciplinary scholars is that we are living in the shadow of the so-called death of Modernity, a complex ideological movement that handicaps Christian scholarship in myriad ways. This ideology considers human reason autonomous (independent from God and his self-revelation) and views the scientific method as the only trustworthy frame of reference for accessing reality. It encourages the specialization of knowledge, is committed to individualism, and has a strong utopian impulse.

Many of modernity’s most positive aspects were fostered by the Christian worldview out of whose soil they grew. However, the Christian worldview has been increasingly abandoned and, as a result, Western scholars have embraced a naturalist metaphysic and epistemology and a secular system of public and scientific discourse. As a result, the university has become a dis-university, having no unifying center and experiencing disciplinary fragmentation.

2. Christian scholars and administrators must work to unify and redirect higher education.

During the past several decades, many Christian scholars have tried to overcome this disunity and disciplinary fragmentation by embarking on a project of “integration.” However, the integration project often is tainted by late modern presuppositions and therefore often is unable to offer a truly Christian account of the academic disciplines.

For this reason, the Transdisciplinary group wishes to go beyond “integration.” We must recognize the ways in which late modernity has reified and isolated the disciplines from one another, and replace the later modern paradigm with a truly Christian one. In order to do so we leverage the Christian Scriptures and worldview toward the end of promoting a Christian “transdisciplinarity.”

What is transdisciplinary scholarship? It is radically Christian scholarship in which each discipline not only views its own discipline from within a Christian frame of reference, but also draws upon the wisdom of the other disciplines. In so doing, Christian scholarship helps bring unity to the ever-increasing specialization and fragmentation of the disciplines. The Transdisciplinary Group aims for “the transposition of each discipline into a higher, ever-increasingly unified order of knowledge and love, based on a Christian metaphysic.”

Transdisciplinary scholarship relies upon certain meta-disciplines (e.g. biblical studies, theology, Christian philosophy) to guide it in building an integrated body of knowledge, understanding, and practice. Instead of merely learning within isolated disciplines, therefore, we are able to bring the disciplines into conversation with one another, with each discipline being enriched, and with new trans-disciplines being created.

3. Christian universities and scholars must ascribe value to specialists and generalists.

We are not arguing that the universities and seminaries should discourage specialized knowledge, but that specialized fields of knowledge should remain in conversation with one another, and should together be informed by certain meta-disciplines (e.g. biblical studies, theology, and Christian philosophy). In other words, the Christian university should seek truly to be a uni-versity, a unified endeavor.

The obstacles to building a transdisciplinary Christian university are many, but not insurmountable. Presidents and Provosts must re-prioritize by hiring faculty members who will invest in the project, providing forums in which professors from various disciplines (e.g. arts, sciences) remain in close conversation with one another, and in which they together converse with biblical scholars, theologians, and Christian philosophers.

Professors must re-prioritize, by investing time and energy in reading more broadly (in the meta-disciplines and in other disciplines) and engaging in their research projects communally. To re-prioritize in this manner poses a challenge, in light of the fact that many scholars are already stretched thin because of their teaching, advising, writing, and committee-attendance. However, the challenge is not insurmountable, and those persons and universities will be rewarded who meet the challenge in order to forge a genuinely transdisciplinary environment.

4. Christian churches must ascribe value to the intellectual life.

Finally, local churches can help radical Christian scholarship to flourish. Many local churches already place value on higher education, but perhaps all of our churches can engage in a more concentrated effort to encourage gifted young people to pursue a calling in higher education. We can help our young people understand how our Christian witness would be significantly enhanced by an increase in the number of scholars and professors who do radically Christian scholarship, by the combined witness of thousands of faithful classroom instructors and researchers who do their work to the glory of God.

Subscribe

Never miss a post! Have all new posts delivered straight to your inbox.

#4 is so important, yes liberalism ad post-modernism have infiltrated even many historically Christian institutions, but rather than fight this onslaught with Christian Scholarship many Evangelicals have retreated abdicating scholarship to secularists and liberals. Historically Churches have pushed research and scholarship further. The reversal of this trend in the last 100 years is disturbing to say the least.

Dr Ashford

as a 60 year old pastor, having a masters degree and a doctor of ministry degree I fully embrace your thoughts in this post. Let me offer a suggestion – as we train pastors/ministers at the seminary level let’s challenge students to read more broadly, to get past the constant bombardment of the idea that a good pastor sees church growth occurring numerically every year, and encourage pastors to plant their lives in one place for the sake of their family and the Kingdom of God. After 25 1/2 years serving the same church I have opportunities in my community that far exceed anything that I might have imagined or dreamed. I am concerned that too many of our seminary graduates are enamored of the idea that they are not successful if they are not serving a large and growing larger church instead of focusing on expanding the kingdom of God.

Just some random thoughts

Pastor Steve, thank you. Those are some wise words.

I am sure all this is well meant but difficult to put into practice. I had an article accepted immediately by BibSac when I submitted it to them July 2016 but in late December when the article was supposedly forthcoming in its January 2017 issue, someone retracted its publication at the eleventh hour without affording me the courtesy if a decent explanation. But I could guess what it was: it was not orthodox enough as the article’s title “Doubting Abraham” would suggest. So I don’t know if radical scholarship would ever be acceptable in our seminaries where the word heresy is irritatingly bandied around all the time. One of the things I have come to realize belatedly is that seminary is not graduate school because dissent and ideas are not welcome if they are heterodox or unorthodox. (And I have been two good graduate schools so I do know a little about what they should look like in terms of intellectual engagement.