Politics in the United States has, for some time, assumed a binary structure. On one side stand the Republicans, many of hold to some form of social conservatism. On the other side stand the Democrats, many of whom hold to some form of social progressivism. But what many Americans fail to see is that conservatism and progressivism are similar in several respects. In their pure forms, both ascribe ultimacy to something other than God. Both lack transcendent norms of their own. And thus, both can lead to a variety of social, cultural, and political ills.

Political Conservatism and Progressivism as Ideologies

Conservatism

Ideological conservatism tends to view a particular cultural heritage as normative, and by extension views social revolutions as the greatest political evil, fearing that macro-level social changes will have unintended negative consequences. Instead of reforming social ills through massive reform agendas or revolutions, they seek to reform by reaching back into the best of their past history and cultural heritage.

Conservatives are open to social reform, of course, because the only way to bring back that elusive golden age is to reform the present one. Political scientist David Koyzis describes the conservative impulse:

If reforms are to be attempted, then they must be small in scale, incremental in pace and firmly grounded in past experience. The conservative prefers to see people attempt to alleviate poverty in their own neighborhoods than to try to eliminate it throughout the entire nation. Because of its local nature, the former is a much more realistic and manageable effort than the latter and is thus more likely to meet with success.

Thus, conservatives want any reforms to be implemented in a careful and deliberate manner.

[Note to reader: In the United States, the word “conservative” is used in narrow and broad senses. This article is addressing conservatism in its narrower sense as a specific political ideology. However, “conservative” can also be used in a broader sense to mean “somebody whose political views tend to fall on the right side of the American political spectrum.” In that sense, I consider myself a conservative as I have written in an article entitled, “How Can a Faithful Evangelical Be a Political Conservative?”]

Progressivism

Ideological progressivism is in some ways the antithesis of conservatism, in that it looks to the future instead of the past, ascribing ultimacy to social reform. While conservatism looks back over its shoulder to a golden age of the past, progressivism tries to peer over the next hill to a golden age of the future. And it is often, though not exclusively, driven by government initiatives. In our American context, progressivism pairs with democratic socialism and whatever is left of liberalism to serve as the heartbeat of the Democratic Party.

Progressivism tends to define itself in contrast to conservatism. For progressives, social conservatism is the primary evil from which society needs to be rescued. To put it simply: progressives are suspicious of the past and optimistic about the future. Positively, progressives rightly recognize certain evils in a given social order. There are always sins of our past that we should avoid repeating, and sins of our present that we must eradicate. But progressives too easily conflate those societal ills with the social order itself. They, like the conservatives, throw the baby out with the dirty bathwater.

Conservatives are wrong to react reflexively and negatively against change. Progressives are wrong to react reflexively and negatively against traditional values. Neither conservation nor progress is the core problem. The core problem is idolatry and its twisting and distorting effect on politics. Every nation in history has proven a lush environment for idols, and every modern political ideology suffers the ill effects of idolatry.

The Problems with Idolatrous Conservatism

Inconsistency

A significant problem with both conservatism and progressivism is that, unlike socialism (on the left) or nationalism (on the right), conservatism and progressivism are time-bound ideologies and as such are always “on the move.” They are not abstract ideologies but contextual responses.

This may embarrass many conservatives, who consider conservative principles immovable and universal. They are not. What counts as “conservatism” in one country will have very little to do with “conservatism” in another country. While conservatives in the United States might be trying to conserve the economic and political policies of Ronald Reagan, conservatives in another country might be trying to revitalize the authoritarian structures of a previous era. What a society aims to conserve can vary wildly depending on the nation and its history. Pure conservatism, as David Koyzis notes, is an ideological parasite that feeds off of other ideologies. It has no identifiable doctrinal position of its own.

Even within a single nation, conservatives have a hard time making strategic alliance with one another. What exactly are we aiming to conserve? Our constitutional order? Wealth? Race? Judeo-Christian morality? Americans are seeing this right now in our country. Some conservatives are more primarily motivated by a free market agenda, others by maintaining “white America,” and yet others by Judeo-Christian moral issues. These competing groups make good tactical allies because they all oppose progressivism, and also because they often have a common desire to conserve their own power and privilege. But they should not be assumed to be ideologically identical.

Lack of Transcendence

Conservatives, despite their high opinion of the past, cannot merely accept all of it uncritically. So when conservatives do criticize their own tradition, as they must, they are forced to rummage around for some norms that transcend history (e.g. opposing slavery). Pure conservatives, therefore, often find themselves in tactical alliance with Christians, even if they cannot stomach a long-term strategic alliance with them. In other words, ideological conservatism can tolerate or even embrace Christianity but only as a means to an end.

But being a “means” to someone else’s “end” is tricky business. Faithful Christians in the United States might be surprised to learn that many of the powerful conservatives in the United States view evangelicals as useful idiots. Christians may fancy that political conservatives stand with them ideologically and strategically, when in fact many conservatives would reject many of the deeply-held convictions of Christians. The alliance is more temporary and tactical, perhaps, than it is long-term or strategic. In upcoming years, as historic Christianity looks more and more strange to American society, Christians may no longer be viewed as useful idiots. We may be seen merely as idiots.

The Problems with Idolatrous Progressivism

Inconsistency

Progressivism, like conservatism, lacks consistency. It is always “on the move,” lacking a doctrinal creed that other ideologies—such as socialism and libertarianism—have. What counts as progressive in one nation may have nothing to do with progressivism in another nation. For instance, progressives in the United States are currently pushing for the expansion of federal regulation into nearly every sector of society. But progressives in China are doing the opposite, pushing for smaller government.

Lack of Transcendence

Like conservatism, progressivism lacks transcendence. When progressives criticize a traditional social order, they have to root around in their culture’s rucksack to find some principle or preference they can elevate to the level of a transcendent standard. But whereas conservatives have the entirety of history from which to borrow their ideas, progressives are at a disadvantage. Their god is the future, but the future is a bit more hazy. Thus they are forced to borrow their standards from another ideology, sometimes almost arbitrarily, to suit their particular agenda.

In the United States, progressives often pair with liberalism in pushing for social reform that frees individuals from regnant social and moral norms. In order for individuals to have maximum autonomy, especially sexual autonomy, progressives seek to redefine what it means to be human, what it means to be a man or a woman, and what it means to be moral.

In relation to humanity, many secular progressives want to redefine what it means to be a human person. Human beings, they argue, are not created in the image and likeness of God (to be created in God’s image would make us accountable to God, after all). Human beings are, instead, advanced animals who differ from animals only in their consciousness and functionality.

In relation to gender, many progressives want to redefine the human person along the lines of ancient Gnosticism (though they hardly ever make this connection overtly). They want to separate a person’s identity from his or her body. In this view, the true “self” is independent of the body to the extent that a man who doesn’t feel like a man can mutilate his body (through gender reassignment surgery) in order to make it more physiologically similar to a woman. We are not men or women by birth, the argument goes, but by choice, and advanced technology is allowing us to become who we truly are.

In relation to morality, many progressives want us to suspend judgment about good and evil As J. Budziszewski notes, progressivism promotes a type of tolerance that requires us to avoid having strong convictions—except, ironically, for the convictions progressives deem good or acceptable. When and where progressivism overturns traditional morality, it attempts to absolve itself from responsibility for decisions: “I am not pro-abortion; I am pro-choice.” “I am not killing a baby. I am removing the products of conception.” In order to overturn social and moral norms, progressives generally push for the government to replace family and religion as the primary agent of moral instruction and formation.

This progressive overturning of the moral order has caused numerous problems in American society. By overturning traditional teaching about human dignity, we have turned the safest place in our society—the womb—into the most dangerous. As public data indicates, we have killed nearly 60 million babies in the last half-century. By attempting to overturn nature, we have turned gender—an aspect of God’s creational design and one of society’s bedrock realities—into an artificial construct devoid of stability or meaning.

As R. R. Reno recently argued, this dismantling of traditional norms and rules is surely one of the reasons for society’s disorientation in general, and destructive behaviors in specific. It is no surprise that in a society as disoriented as ours, suicide and drug-related deaths are on the rise. We no longer have certainty about the most basic facts of life.

Conclusion

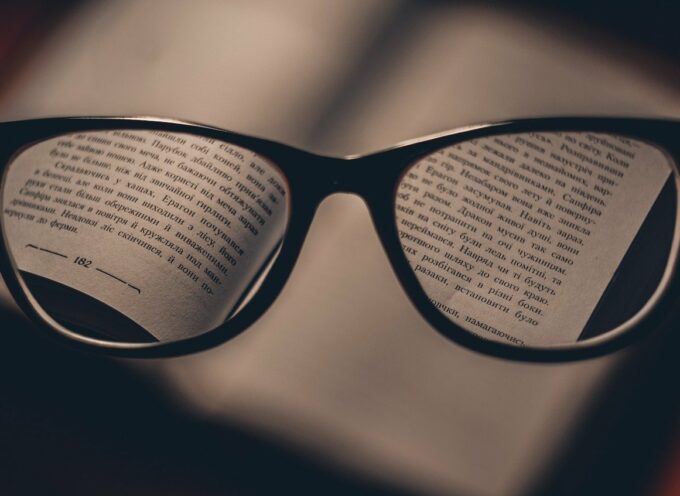

Christians must evaluate our cultural heritage to determine what we think is worth conserving and what needs to be rejected so that we can progress beyond it. And, as I argue in Letters to an American Christian, this sort of evaluation must be made primarily by viewing the world through the lens of the Christian worldview rather than the political narrative of some cable news network. In other words, standing alone, conservatism and progressivism are both errant and even idolatrous.

Subscribe

Never miss a post! Have all new posts delivered straight to your inbox.